T3BlbitTYW5zOjgwMA==

LnRiLWZpZWxkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGQ9IjM2ZjY1NDA1OWY5ZmRhNzJkODExMzQ1YWE2YTA2MDc5Il0geyBmb250LXNpemU6IDEycHg7IH0gIC50Yi1maWVsZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWZpZWxkPSIzNmY2NTQwNTlmOWZkYTcyZDgxMTM0NWFhNmEwNjA3OSJdIGEgeyB0ZXh0LWRlY29yYXRpb246IG5vbmU7IH0gaDIudGItaGVhZGluZ1tkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWhlYWRpbmc9ImFjZjQ2YTU0NzE5NWE1YTZkNjY3NTY5MWZhYWYzMTJmIl0gIHsgZm9udC1zaXplOiAxMnB4O2xpbmUtaGVpZ2h0OiAxNnB4O2NvbG9yOiByZ2JhKCAwLCAwLCAwLCAxICk7IH0gIGgyLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSJhY2Y0NmE1NDcxOTVhNWE2ZDY2NzU2OTFmYWFmMzEyZiJdIGEgIHsgdGV4dC1kZWNvcmF0aW9uOiBub25lOyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSJhZTM1OGZhMTcyMDQyNDUyYjMyNGVhZjBhYzVkNGRmMCJdIHsgcGFkZGluZzogMCAyNXB4IDI1cHggMjVweDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lcltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lcj0iMjBhMTU1OTYwNWM3NmZjYjc0YTkxODczOWU2NWVjNTYiXSB7IHBhZGRpbmc6IDIwcHggMjVweCAyNXB4IDI1cHg7bWFyZ2luLXRvcDogMjBweDtib3JkZXItdG9wOiAxcHggc29saWQgcmdiYSggMjM2LCAyMzYsIDIzNiwgMSApO2JvcmRlci1yaWdodDogMHB4IHNvbGlkIHJnYmEoIDIzNiwgMjM2LCAyMzYsIDEgKTtib3JkZXItYm90dG9tOiAwcHggc29saWQgcmdiYSggMjM2LCAyMzYsIDIzNiwgMSApO2JvcmRlci1sZWZ0OiAwcHggc29saWQgcmdiYSggMjM2LCAyMzYsIDIzNiwgMSApOyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSI4ODYzM2MxNzJjMTE5NmYzYWQ2Zjk4YTNkYTRlY2UyYSJdIHsgYmFja2dyb3VuZDogcmdiYSggMjM2LCAyMzYsIDIzNiwgMSApO3BhZGRpbmc6IDI1cHg7bWFyZ2luLXRvcDogMDsgfSAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3B2LXZpZXctb3V0cHV0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC12aWV3cy12aWV3LWVkaXRvcj0iZDE3MTE4OTZkODY1OWRmMDNhMWFiYmNhOTczYWRkZjciXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSg0biArIDEpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDEgfSAud3B2LXZpZXctb3V0cHV0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC12aWV3cy12aWV3LWVkaXRvcj0iZDE3MTE4OTZkODY1OWRmMDNhMWFiYmNhOTczYWRkZjciXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSg0biArIDIpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDIgfSAud3B2LXZpZXctb3V0cHV0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC12aWV3cy12aWV3LWVkaXRvcj0iZDE3MTE4OTZkODY1OWRmMDNhMWFiYmNhOTczYWRkZjciXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSg0biArIDMpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDMgfSAud3B2LXZpZXctb3V0cHV0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC12aWV3cy12aWV3LWVkaXRvcj0iZDE3MTE4OTZkODY1OWRmMDNhMWFiYmNhOTczYWRkZjciXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSg0biArIDQpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDQgfSAud3B2LXZpZXctb3V0cHV0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC12aWV3cy12aWV3LWVkaXRvcj0iZDE3MTE4OTZkODY1OWRmMDNhMWFiYmNhOTczYWRkZjciXSAuanMtd3B2LWxvb3Atd3JhcHBlciA+IC50Yi1ncmlkIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC4yNWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC4yNWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC4yNWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC4yNWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwdi1wYWdpbmF0aW9uLW5hdi1saW5rc1tkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtdmlld3Mtdmlldy1wYWdpbmF0aW9uLWJsb2NrPSI5ZTM1MjNmY2VlYTYzOWUyNTEzMzhjNjY5MmZjNzllMSJdIHsgdGV4dC1hbGlnbjogY2VudGVyO2p1c3RpZnktY29udGVudDogY2VudGVyO3BhZGRpbmctdG9wOiAzMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gLndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlLnRiLWltYWdlW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtaW1hZ2U9ImE2NDIyMWU2ZGQ0N2ZiMWE1YzQxNjYyMzZjZmQ3MDc2Il0geyBtYXgtd2lkdGg6IDEwMCU7IH0gIGgyLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSI5MmY2YmY1MGEwN2MxMzAyNTk2MmI5NjRiNDQxYjZkZiJdIGEgIHsgdGV4dC1kZWNvcmF0aW9uOiBub25lOyB9ICBoMi50Yi1oZWFkaW5nW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtaGVhZGluZz0iYjhmYTU4MTgyODVlZDVlNTkwN2RlZGMzNjBjOWQ2ZWIiXSBhICB7IHRleHQtZGVjb3JhdGlvbjogbm9uZTsgfSAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219IC53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZS50Yi1pbWFnZVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWltYWdlPSI2MWExZDkzMTJhOTU1N2JlZjhhMDAzZDcwODc2NWRiOSJdIHsgbWF4LXdpZHRoOiAxMDAlOyB9ICBoMi50Yi1oZWFkaW5nW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtaGVhZGluZz0iYjlhMzFkZjdiNzRjYWMyMjE2ZWIzZDYzMGY4NDhhMzIiXSBhICB7IHRleHQtZGVjb3JhdGlvbjogbm9uZTsgfSBoMi50Yi1oZWFkaW5nW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtaGVhZGluZz0iMTExYzQyM2E1NzAwN2U1OGYwYmY2N2VhZmU4YzY0MWIiXSAgeyBmb250LXNpemU6IDIwcHg7Zm9udC1mYW1pbHk6IE9wZW4gU2Fucztmb250LXdlaWdodDogODAwO2NvbG9yOiByZ2JhKCAyMTcsIDgyLCAzNywgMSApO3BhZGRpbmctbGVmdDogMjBweDsgfSAgaDIudGItaGVhZGluZ1tkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWhlYWRpbmc9IjExMWM0MjNhNTcwMDdlNThmMGJmNjdlYWZlOGM2NDFiIl0gYSAgeyBjb2xvcjogcmdiYSggMjE3LCA4MiwgMzcsIDEgKTt0ZXh0LWRlY29yYXRpb246IG5vbmU7IH0gLnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImZkMmYwZDAzOGYwMjI0NzliNWZkYWIyODNlOTc2YmUyIl0geyBwYWRkaW5nLXRvcDogMjBweDttYXJnaW4tdG9wOiAwO2dyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuMjRmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuNzZmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJmZDJmMGQwMzhmMDIyNDc5YjVmZGFiMjgzZTk3NmJlMiJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJmZDJmMGQwMzhmMDIyNDc5YjVmZGFiMjgzZTk3NmJlMiJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMikgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMiB9ICAudGItZmllbGRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1maWVsZD0iNWE5NTM4ZGEwOWY3M2M3YTE1ZjIwMzliNzQ2NGQ4NzYiXSBhIHsgdGV4dC1kZWNvcmF0aW9uOiBub25lOyB9ICAudGItZmllbGRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1maWVsZD0iNjI2YWJjZjU3MzJlYzcxMTU0OWY5NDc2ODQ1MzRmYmQiXSBhIHsgdGV4dC1kZWNvcmF0aW9uOiBub25lOyB9ICAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219IC53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZS50Yi1pbWFnZVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWltYWdlPSJiN2E2ODQ0MzhlZTA4ZTJkNWQxMWVhM2JmYzViNjljMyJdIHsgbWF4LXdpZHRoOiAxMDAlOyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZS50Yi1pbWFnZVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWltYWdlPSJiN2E2ODQ0MzhlZTA4ZTJkNWQxMWVhM2JmYzViNjljMyJdIGltZyB7IHBhZGRpbmctdG9wOiAyMHB4O3BhZGRpbmctYm90dG9tOiAyMHB4OyB9ICAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lcltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lcj0iOTkwZTIxMWJmZDlhMWRlOWZmNmVhY2IxMWQ0ZTQ5MWMiXSB7IHBhZGRpbmc6IDQ1cHggMjVweCAxMHB4IDE2cHg7IH0gICAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iZGUwYTg4OWU1NTU5NmRlODY4NWJmNTc3YzQ4ZDAwYWIiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9ImQ5ZDkzZWVhZTgyZTVmMjg0NDMzMjM3Njc0ZDQxZDMwIl0geyBwYWRkaW5nOiAyMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImU4YzllYjY3N2VmNzY3YmE0YjRiNDFiNzYxN2UwOTgzIl0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjY2NWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC4zMzVmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJlOGM5ZWI2NzdlZjc2N2JhNGI0YjQxYjc2MTdlMDk4MyJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJlOGM5ZWI2NzdlZjc2N2JhNGI0YjQxYjc2MTdlMDk4MyJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMikgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMiB9IC50Yi1maWVsZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWZpZWxkPSI4ODk1YjIzMTljNzgxMDAzZTEzZDA4Yjk1NWEzOWE1YiJdIHsgZm9udC1zaXplOiAxMnB4OyB9ICAudGItZmllbGRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1maWVsZD0iODg5NWIyMzE5Yzc4MTAwM2UxM2QwOGI5NTVhMzlhNWIiXSBhIHsgdGV4dC1kZWNvcmF0aW9uOiBub25lOyB9IGgyLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSJmMzkzYjk4ODk5MTk1NTI3ZmZjNjEwNWE3MzcwMGJjNyJdICB7IGxpbmUtaGVpZ2h0OiAxNnB4OyB9ICBoMi50Yi1oZWFkaW5nW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtaGVhZGluZz0iZjM5M2I5ODg5OTE5NTUyN2ZmYzYxMDVhNzM3MDBiYzciXSBhICB7IHRleHQtZGVjb3JhdGlvbjogbm9uZTsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lcltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lcj0iZWQzODMyYWE2MjAxY2JlYzViMWU1YjkwMmRjMDY3ZTIiXSB7IHBhZGRpbmc6IDI1cHg7IH0gLnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImI0MzIxNzE4MTI0MGMwODQyMzdmYjlmM2FhMzc0OGI5Il0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjI3MzMzMzMzMzMzMzMzZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjQ0MzMzMzMzMzMzMzMzZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjI4MzMzMzMzMzMzMzMzZnIpO2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDogMnB4O2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iYjQzMjE3MTgxMjQwYzA4NDIzN2ZiOWYzYWEzNzQ4YjkiXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSgzbiArIDEpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDEgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iYjQzMjE3MTgxMjQwYzA4NDIzN2ZiOWYzYWEzNzQ4YjkiXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSgzbiArIDIpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDIgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iYjQzMjE3MTgxMjQwYzA4NDIzN2ZiOWYzYWEzNzQ4YjkiXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSgzbiArIDMpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDMgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iNjE5MWE5ZGNjYjEwZjNhZWIzYmE0YTljNTE3YWIyZTAiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWJ1dHRvbntjb2xvcjojZjFmMWYxfS50Yi1idXR0b24tLWxlZnR7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpsZWZ0fS50Yi1idXR0b24tLWNlbnRlcnt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmNlbnRlcn0udGItYnV0dG9uLS1yaWdodHt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOnJpZ2h0fS50Yi1idXR0b25fX2xpbmt7Y29sb3I6aW5oZXJpdDtjdXJzb3I6cG9pbnRlcjtkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1ibG9jaztsaW5lLWhlaWdodDoxMDAlO3RleHQtZGVjb3JhdGlvbjpub25lICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpjZW50ZXI7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjphbGwgMC4zcyBlYXNlfS50Yi1idXR0b25fX2xpbms6aG92ZXIsLnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fbGluazpmb2N1cywudGItYnV0dG9uX19saW5rOnZpc2l0ZWR7Y29sb3I6aW5oZXJpdH0udGItYnV0dG9uX19saW5rOmhvdmVyIC50Yi1idXR0b25fX2NvbnRlbnQsLnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fbGluazpmb2N1cyAudGItYnV0dG9uX19jb250ZW50LC50Yi1idXR0b25fX2xpbms6dmlzaXRlZCAudGItYnV0dG9uX19jb250ZW50e2ZvbnQtZmFtaWx5OmluaGVyaXQ7Zm9udC1zdHlsZTppbmhlcml0O2ZvbnQtd2VpZ2h0OmluaGVyaXQ7bGV0dGVyLXNwYWNpbmc6aW5oZXJpdDt0ZXh0LWRlY29yYXRpb246aW5oZXJpdDt0ZXh0LXNoYWRvdzppbmhlcml0O3RleHQtdHJhbnNmb3JtOmluaGVyaXR9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fY29udGVudHt2ZXJ0aWNhbC1hbGlnbjptaWRkbGU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjphbGwgMC4zcyBlYXNlfS50Yi1idXR0b25fX2ljb257dHJhbnNpdGlvbjphbGwgMC4zcyBlYXNlO2Rpc3BsYXk6aW5saW5lLWJsb2NrO3ZlcnRpY2FsLWFsaWduOm1pZGRsZTtmb250LXN0eWxlOm5vcm1hbCAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1idXR0b25fX2ljb246OmJlZm9yZXtjb250ZW50OmF0dHIoZGF0YS1mb250LWNvZGUpO2ZvbnQtd2VpZ2h0Om5vcm1hbCAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1idXR0b25fX2xpbmt7YmFja2dyb3VuZC1jb2xvcjojNDQ0O2JvcmRlci1yYWRpdXM6MC4zZW07Zm9udC1zaXplOjEuM2VtO21hcmdpbi1ib3R0b206MC43NmVtO3BhZGRpbmc6MC41NWVtIDEuNWVtIDAuNTVlbX0gLnRiLWJ1dHRvbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWJ1dHRvbj0iNzJmMjhiODNlZDhmZWE0ZjgzMDJlNGQ4ZjNkOGRkMTciXSAudGItYnV0dG9uX19pY29uIHsgZm9udC1mYW1pbHk6IGRhc2hpY29uczsgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iYTgyYTc1NzBhODY3MzM4YTU2MTAwMDAyNzg0YTI3ZjAiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjVkYWU5YTZhYmRkNTRjZGI3Y2E0MmQyYzYxMmU2OWJhIl0geyBwYWRkaW5nLXJpZ2h0OiAzMHB4O2Rpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iZDFmODVhYzAzNTgwMGNlY2U0MjQwMTg2N2E2MDA3ZGIiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMDcxNGFjMzM1YmRkZmE2NDk4MDBiYjcyYWI2ZTQyM2QiXSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuNjRmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuMzZmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSIwNzE0YWMzMzViZGRmYTY0OTgwMGJiNzJhYjZlNDIzZCJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSIwNzE0YWMzMzViZGRmYTY0OTgwMGJiNzJhYjZlNDIzZCJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMikgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMiB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSJmNmUwZWIwYTU5MzFiZDBmOTQwNDI1NzMxYjYzMzczNSJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iMzAzNGZiZTg4NmMxMTA1NGU5NWI0NmIwOWQzZTQxMTIiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iOTFiMmQ5ODJiNTQxMDdhNzRkZDY4M2M3OWFkMzc3YWUiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSBAbWVkaWEgb25seSBzY3JlZW4gYW5kIChtYXgtd2lkdGg6IDc4MXB4KSB7ICAgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30udGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfS50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwdi12aWV3LW91dHB1dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtdmlld3Mtdmlldy1lZGl0b3I9ImQxNzExODk2ZDg2NTlkZjAzYTFhYmJjYTk3M2FkZGY3Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoM24gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwdi12aWV3LW91dHB1dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtdmlld3Mtdmlldy1lZGl0b3I9ImQxNzExODk2ZDg2NTlkZjAzYTFhYmJjYTk3M2FkZGY3Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoM24gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLndwdi12aWV3LW91dHB1dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtdmlld3Mtdmlldy1lZGl0b3I9ImQxNzExODk2ZDg2NTlkZjAzYTFhYmJjYTk3M2FkZGY3Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoM24gKyAzKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAzIH0gLndwdi12aWV3LW91dHB1dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtdmlld3Mtdmlldy1lZGl0b3I9ImQxNzExODk2ZDg2NTlkZjAzYTFhYmJjYTk3M2FkZGY3Il0gLmpzLXdwdi1sb29wLXdyYXBwZXIgPiAudGItZ3JpZCB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuMzMzM2ZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC4zMzMzZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjMzMzNmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gIC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gIC50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJmZDJmMGQwMzhmMDIyNDc5YjVmZGFiMjgzZTk3NmJlMiJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC41ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJmZDJmMGQwMzhmMDIyNDc5YjVmZGFiMjgzZTk3NmJlMiJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJmZDJmMGQwMzhmMDIyNDc5YjVmZGFiMjgzZTk3NmJlMiJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMikgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMiB9ICAgIC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gIC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSJkZTBhODg5ZTU1NTk2ZGU4Njg1YmY1NzdjNDhkMDBhYiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfS50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImU4YzllYjY3N2VmNzY3YmE0YjRiNDFiNzYxN2UwOTgzIl0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuNWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImU4YzllYjY3N2VmNzY3YmE0YjRiNDFiNzYxN2UwOTgzIl0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImU4YzllYjY3N2VmNzY3YmE0YjRiNDFiNzYxN2UwOTgzIl0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gICAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfS50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJiNDMyMTcxODEyNDBjMDg0MjM3ZmI5ZjNhYTM3NDhiOSJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC4zMzMzZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjMzMzNmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuMzMzM2ZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImI0MzIxNzE4MTI0MGMwODQyMzdmYjlmM2FhMzc0OGI5Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoM24gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImI0MzIxNzE4MTI0MGMwODQyMzdmYjlmM2FhMzc0OGI5Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoM24gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImI0MzIxNzE4MTI0MGMwODQyMzdmYjlmM2FhMzc0OGI5Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoM24gKyAzKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAzIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjYxOTFhOWRjY2IxMGYzYWViM2JhNGE5YzUxN2FiMmUwIl0geyBkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IC50Yi1idXR0b257Y29sb3I6I2YxZjFmMX0udGItYnV0dG9uLS1sZWZ0e3RleHQtYWxpZ246bGVmdH0udGItYnV0dG9uLS1jZW50ZXJ7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbi0tcmlnaHR7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpyaWdodH0udGItYnV0dG9uX19saW5re2NvbG9yOmluaGVyaXQ7Y3Vyc29yOnBvaW50ZXI7ZGlzcGxheTppbmxpbmUtYmxvY2s7bGluZS1oZWlnaHQ6MTAwJTt0ZXh0LWRlY29yYXRpb246bm9uZSAhaW1wb3J0YW50O3RleHQtYWxpZ246Y2VudGVyO3RyYW5zaXRpb246YWxsIDAuM3MgZWFzZX0udGItYnV0dG9uX19saW5rOmhvdmVyLC50Yi1idXR0b25fX2xpbms6Zm9jdXMsLnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fbGluazp2aXNpdGVke2NvbG9yOmluaGVyaXR9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fbGluazpob3ZlciAudGItYnV0dG9uX19jb250ZW50LC50Yi1idXR0b25fX2xpbms6Zm9jdXMgLnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fY29udGVudCwudGItYnV0dG9uX19saW5rOnZpc2l0ZWQgLnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fY29udGVudHtmb250LWZhbWlseTppbmhlcml0O2ZvbnQtc3R5bGU6aW5oZXJpdDtmb250LXdlaWdodDppbmhlcml0O2xldHRlci1zcGFjaW5nOmluaGVyaXQ7dGV4dC1kZWNvcmF0aW9uOmluaGVyaXQ7dGV4dC1zaGFkb3c6aW5oZXJpdDt0ZXh0LXRyYW5zZm9ybTppbmhlcml0fS50Yi1idXR0b25fX2NvbnRlbnR7dmVydGljYWwtYWxpZ246bWlkZGxlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246YWxsIDAuM3MgZWFzZX0udGItYnV0dG9uX19pY29ue3RyYW5zaXRpb246YWxsIDAuM3MgZWFzZTtkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1ibG9jazt2ZXJ0aWNhbC1hbGlnbjptaWRkbGU7Zm9udC1zdHlsZTpub3JtYWwgIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItYnV0dG9uX19pY29uOjpiZWZvcmV7Y29udGVudDphdHRyKGRhdGEtZm9udC1jb2RlKTtmb250LXdlaWdodDpub3JtYWwgIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItYnV0dG9uX19saW5re2JhY2tncm91bmQtY29sb3I6IzQ0NDtib3JkZXItcmFkaXVzOjAuM2VtO2ZvbnQtc2l6ZToxLjNlbTttYXJnaW4tYm90dG9tOjAuNzZlbTtwYWRkaW5nOjAuNTVlbSAxLjVlbSAwLjU1ZW19LndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49ImE4MmE3NTcwYTg2NzMzOGE1NjEwMDAwMjc4NGEyN2YwIl0geyBkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSI1ZGFlOWE2YWJkZDU0Y2RiN2NhNDJkMmM2MTJlNjliYSJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjA3MTRhYzMzNWJkZGZhNjQ5ODAwYmI3MmFiNmU0MjNkIl0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuNWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjA3MTRhYzMzNWJkZGZhNjQ5ODAwYmI3MmFiNmU0MjNkIl0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjA3MTRhYzMzNWJkZGZhNjQ5ODAwYmI3MmFiNmU0MjNkIl0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49ImY2ZTBlYjBhNTkzMWJkMGY5NDA0MjU3MzFiNjMzNzM1Il0geyBkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIzMDM0ZmJlODg2YzExMDU0ZTk1YjQ2YjA5ZDNlNDExMiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219IH0gQG1lZGlhIG9ubHkgc2NyZWVuIGFuZCAobWF4LXdpZHRoOiA1OTlweCkgeyAgIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99LnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30udGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfS50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cHYtdmlldy1vdXRwdXRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LXZpZXdzLXZpZXctZWRpdG9yPSJkMTcxMTg5NmQ4NjU5ZGYwM2ExYWJiY2E5NzNhZGRmNyJdICA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSgxbisxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwdi12aWV3LW91dHB1dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtdmlld3Mtdmlldy1lZGl0b3I9ImQxNzExODk2ZDg2NTlkZjAzYTFhYmJjYTk3M2FkZGY3Il0gLmpzLXdwdi1sb29wLXdyYXBwZXIgPiAudGItZ3JpZCB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gIC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gIC50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJmZDJmMGQwMzhmMDIyNDc5YjVmZGFiMjgzZTk3NmJlMiJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImZkMmYwZDAzOGYwMjI0NzliNWZkYWIyODNlOTc2YmUyIl0gID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDFuKzEpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDEgfSAgICAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99ICAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iZGUwYTg4OWU1NTU5NmRlODY4NWJmNTc3YzQ4ZDAwYWIiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30udGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfS50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJlOGM5ZWI2NzdlZjc2N2JhNGI0YjQxYjc2MTdlMDk4MyJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImU4YzllYjY3N2VmNzY3YmE0YjRiNDFiNzYxN2UwOTgzIl0gID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDFuKzEpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDEgfSAgIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImI0MzIxNzE4MTI0MGMwODQyMzdmYjlmM2FhMzc0OGI5Il0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iYjQzMjE3MTgxMjQwYzA4NDIzN2ZiOWYzYWEzNzQ4YjkiXSAgPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMW4rMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSI2MTkxYTlkY2NiMTBmM2FlYjNiYTRhOWM1MTdhYjJlMCJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItYnV0dG9ue2NvbG9yOiNmMWYxZjF9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbi0tbGVmdHt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmxlZnR9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbi0tY2VudGVye3RleHQtYWxpZ246Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1idXR0b24tLXJpZ2h0e3RleHQtYWxpZ246cmlnaHR9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fbGlua3tjb2xvcjppbmhlcml0O2N1cnNvcjpwb2ludGVyO2Rpc3BsYXk6aW5saW5lLWJsb2NrO2xpbmUtaGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7dGV4dC1kZWNvcmF0aW9uOm5vbmUgIWltcG9ydGFudDt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmNlbnRlcjt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOmFsbCAwLjNzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fbGluazpob3ZlciwudGItYnV0dG9uX19saW5rOmZvY3VzLC50Yi1idXR0b25fX2xpbms6dmlzaXRlZHtjb2xvcjppbmhlcml0fS50Yi1idXR0b25fX2xpbms6aG92ZXIgLnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fY29udGVudCwudGItYnV0dG9uX19saW5rOmZvY3VzIC50Yi1idXR0b25fX2NvbnRlbnQsLnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fbGluazp2aXNpdGVkIC50Yi1idXR0b25fX2NvbnRlbnR7Zm9udC1mYW1pbHk6aW5oZXJpdDtmb250LXN0eWxlOmluaGVyaXQ7Zm9udC13ZWlnaHQ6aW5oZXJpdDtsZXR0ZXItc3BhY2luZzppbmhlcml0O3RleHQtZGVjb3JhdGlvbjppbmhlcml0O3RleHQtc2hhZG93OmluaGVyaXQ7dGV4dC10cmFuc2Zvcm06aW5oZXJpdH0udGItYnV0dG9uX19jb250ZW50e3ZlcnRpY2FsLWFsaWduOm1pZGRsZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOmFsbCAwLjNzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9faWNvbnt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOmFsbCAwLjNzIGVhc2U7ZGlzcGxheTppbmxpbmUtYmxvY2s7dmVydGljYWwtYWxpZ246bWlkZGxlO2ZvbnQtc3R5bGU6bm9ybWFsICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9faWNvbjo6YmVmb3Jle2NvbnRlbnQ6YXR0cihkYXRhLWZvbnQtY29kZSk7Zm9udC13ZWlnaHQ6bm9ybWFsICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fbGlua3tiYWNrZ3JvdW5kLWNvbG9yOiM0NDQ7Ym9yZGVyLXJhZGl1czowLjNlbTtmb250LXNpemU6MS4zZW07bWFyZ2luLWJvdHRvbTowLjc2ZW07cGFkZGluZzowLjU1ZW0gMS41ZW0gMC41NWVtfS53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSJhODJhNzU3MGE4NjczMzhhNTYxMDAwMDI3ODRhMjdmMCJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iNWRhZTlhNmFiZGQ1NGNkYjdjYTQyZDJjNjEyZTY5YmEiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfS50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSIwNzE0YWMzMzViZGRmYTY0OTgwMGJiNzJhYjZlNDIzZCJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjA3MTRhYzMzNWJkZGZhNjQ5ODAwYmI3MmFiNmU0MjNkIl0gID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDFuKzEpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDEgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iZjZlMGViMGE1OTMxYmQwZjk0MDQyNTczMWI2MzM3MzUiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjMwMzRmYmU4ODZjMTEwNTRlOTViNDZiMDlkM2U0MTEyIl0geyBkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gfSA=

Raúl Vergara, Cofounder and International Programs Director, Global Leaders Program; Graduate, La Escuela Experimental de Música Jorge Peña Hen

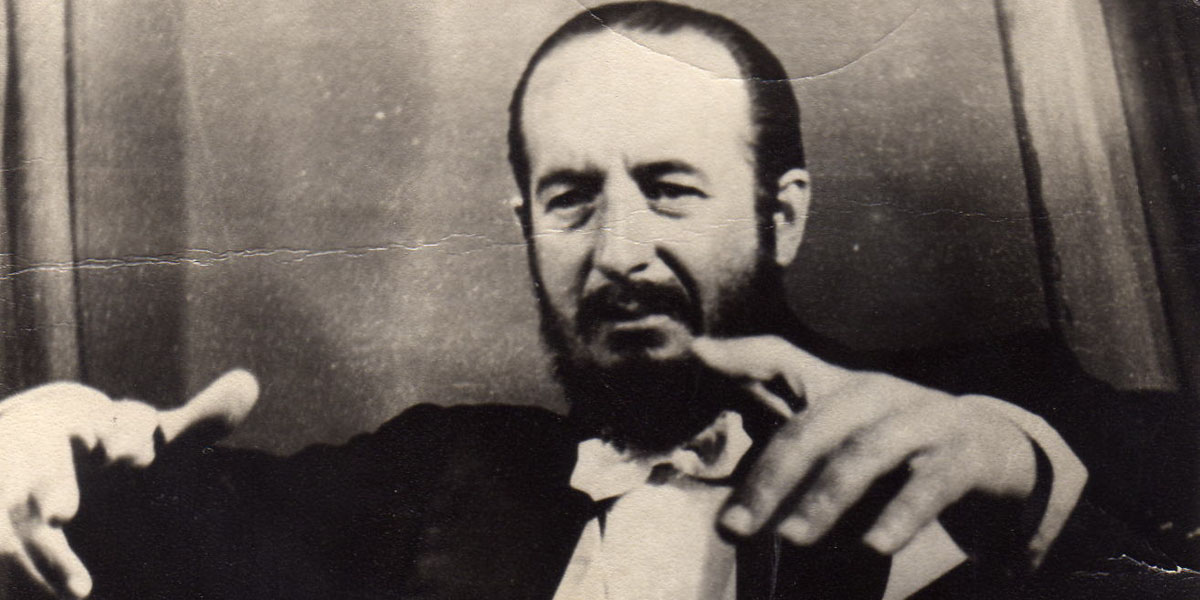

Jorge Peña Hen. Credit: Catiray.

Winter 2012, La Serena, Chile: an overcast but mild day, with a soft, chilly ocean breeze from the Pacific Ocean’s Humboldt Current. I was with Victor Hugo, a high school friend of mine who had put his trumpet aside to study law and journalism at the university before becoming the editor of a local newspaper. We were both accompanying Don Juan Orrego Salas, a 93-year-old gentleman who was visiting our city to pay a posthumous tribute to a dear friend of his, to whom he had never gotten to say goodbye in person. We bought a bouquet of flowers and entered the front gate of the cemetery without an exact knowledge of where we were going—which was not a problem, since everyone we passed knew the precise location of the memorial to Jorge Peña Hen.

My first memory of that name is from 1992. I was 12 years old. It had not been long since the military regime had ended; wounds from this period remained, and many of us were still afraid. One day, without ceremony, a new sign appeared over the entrance of my school: “Escuela Experimental de Música Jorge Peña Hen.” At first, I thought it was inconvenient that the name of the school, which already seemed overly long to me, was now to be further extended by adding someone’s full name. In my ignorance, I asked my classmates: “Who is this Jorge Peña Hen?”

Dear readers, if you happen to share my childhood ignorance: Chilean composer and orchestra director Jorge Peña Hen devoted his life to music and to breaking established social patterns through music education. He received his formal musical training at the Conservatory of Music of the University of Chile, where he studied with the most important musical figures of his time, including a young Juan Orrego Salas. His natural leadership and tireless entrepreneurial spirit led him into a life of musical activism that had a profound transformative effect, unparalleled in Latin America at that time. Peña Hen’s legacy includes the launching of a musical society, a polyphonic choir, Christmas altarpieces, a music conservatory, a professional orchestra, youth orchestras, an experimental school of music, and music tours around Chile as well as abroad.

During a two-month trip to the United States in the winter of 1963, Peña Hen visited various musical and academic training centers, with a particular interest in musical work with adolescents. He marveled at the way U.S. high schools incorporated group musical activities, including an important expansion of orchestras and symphonic bands, into the academic curriculum. He returned to La Serena to develop a sustainable musical development plan for the city. Convinced that it was crucial to develop good foundations for music education, he dedicated himself to the training of young musicians from an early age. Thanks to his influence, the first Youth Orchestra of Latin America made its debut in Chile in December 1964.

Don Orrego (with cane) with Orchestra of the Americas, La Serena, Chile 2012. Credit: Orchestra of the Americas Group. In the morning of September 11, 1973, the entire country awakened in great shock to a coup d’état, the sudden death of the president, and the establishment of a military junta. A few days later, Jorge Peña Hen was arrested and tortured. Falsely accused of entering and distributing firearms in the country, and without a proper trial, the illustrious son of La Serena was shot by the town’s military regiment alongside 14 other people who were accused of opposing the regime. It was the afternoon of October 16, 1973.

Victor and I walked with Don Orrego, who relied on his cane to cross the 500-meter stretch toward the end of the cemetery. There stood a memorial dedicated to the “Detained and Disappeared” victims of Pinochet’s military dictatorship. This place, where a picturesque monolith can be found today, was once a mass grave for the 15 bodies shot on that day under orders of the infamous Caravana de la Muerte. Jorge Peña Hen’s body was found among the dead.

Don Juan put aside his cane, and, leaning on his right hand, took a seat in front of the memorial, contemplating his memories for a long moment. Only the ocean wind dared to disturb the solemn silence, as Victor and I watched him delve deeply into his past. After a while, visibly moved, he broke the silence with a few tenuous words, as if he were whispering only to himself: “Poor Jorge… I still can’t believe it.”

Then, remembering we were there, he confided, “I was actually the person who got Jorge Peña Hen his invitation to go to the United States.”

We knew that Orrego Salas had completed his postgraduate education in the United States, including studies at Columbia and Princeton Universities, and that at Tanglewood, he cultivated friendships with Aaron Copland and other distinguished Latin American musicians, including the iconic composer Alberto Ginastera. Now, he told us the next thread of his story.

“The U.S. government and the Rockefeller Foundation had agreed to launch a Latin American music study center in Washington, D.C. They contacted Aaron Copland, who put me on a list of potential candidates for the position of its director. Luckily for me, I was the first person interviewed… I accepted the position but insisted that the center must be affiliated with a university, to prevent it from becoming a political instrument. They agreed.”

Thus did Mr. Orrego Salas become the Director of the Latin American Music Center at Indiana University, which he developed into the largest source of Latin American musical works of the 20th century—and where he once brought his young student Jorge Peña Hen.

Suddenly, my brain was spinning. In an accelerated way, as if I were rewinding the cassette tape of my cultural history, I began to see how everything was intertwined—connecting me back to Orrego Salas, Peña Hen, Copland, and later José Antonio Abreu. I saw how an act by the noble 93-year-old man next to me had influenced the life of Peña Hen, who then became the catalyst for a worldwide movement of the democratization of access to music education, known to us as El Sistema.

And I saw how each one of us, the thousands of musicians and educators around the globe who follow in their footsteps, have been directly or indirectly connected to their work.

Victor and I were fortunate to walk and share in this profound historical reminiscence with Don Juan Orrego Salas; this turned out to be his last visit to his country. His stay in La Serena concluded with a concert at the Monumental Coliseum of the city, performed by Timothy Chooi and the Youth Orchestra of the Americas (now Orchestra of the Americas), offering the thousands of attendees a vindicating tribute to his former student, the forerunner of the Latin American youth orchestra movement: Jorge Peña Hen.

In memory of Don Juan Orrego Salas (January 18, 1919 – November 24, 2019)