T3BlbitTYW5zOjgwMA==

LnRiLWZpZWxkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGQ9IjM2ZjY1NDA1OWY5ZmRhNzJkODExMzQ1YWE2YTA2MDc5Il0geyBmb250LXNpemU6IDEycHg7IH0gIC50Yi1maWVsZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWZpZWxkPSIzNmY2NTQwNTlmOWZkYTcyZDgxMTM0NWFhNmEwNjA3OSJdIGEgeyB0ZXh0LWRlY29yYXRpb246IG5vbmU7IH0gaDIudGItaGVhZGluZ1tkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWhlYWRpbmc9ImFjZjQ2YTU0NzE5NWE1YTZkNjY3NTY5MWZhYWYzMTJmIl0gIHsgZm9udC1zaXplOiAxMnB4O2xpbmUtaGVpZ2h0OiAxNnB4O2NvbG9yOiByZ2JhKCAwLCAwLCAwLCAxICk7IH0gIGgyLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSJhY2Y0NmE1NDcxOTVhNWE2ZDY2NzU2OTFmYWFmMzEyZiJdIGEgIHsgdGV4dC1kZWNvcmF0aW9uOiBub25lOyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSJhZTM1OGZhMTcyMDQyNDUyYjMyNGVhZjBhYzVkNGRmMCJdIHsgcGFkZGluZzogMCAyNXB4IDI1cHggMjVweDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lcltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lcj0iMjBhMTU1OTYwNWM3NmZjYjc0YTkxODczOWU2NWVjNTYiXSB7IHBhZGRpbmc6IDIwcHggMjVweCAyNXB4IDI1cHg7bWFyZ2luLXRvcDogMjBweDtib3JkZXItdG9wOiAxcHggc29saWQgcmdiYSggMjM2LCAyMzYsIDIzNiwgMSApO2JvcmRlci1yaWdodDogMHB4IHNvbGlkIHJnYmEoIDIzNiwgMjM2LCAyMzYsIDEgKTtib3JkZXItYm90dG9tOiAwcHggc29saWQgcmdiYSggMjM2LCAyMzYsIDIzNiwgMSApO2JvcmRlci1sZWZ0OiAwcHggc29saWQgcmdiYSggMjM2LCAyMzYsIDIzNiwgMSApOyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSI4ODYzM2MxNzJjMTE5NmYzYWQ2Zjk4YTNkYTRlY2UyYSJdIHsgYmFja2dyb3VuZDogcmdiYSggMjM2LCAyMzYsIDIzNiwgMSApO3BhZGRpbmc6IDI1cHg7bWFyZ2luLXRvcDogMDsgfSAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3B2LXZpZXctb3V0cHV0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC12aWV3cy12aWV3LWVkaXRvcj0iZDE3MTE4OTZkODY1OWRmMDNhMWFiYmNhOTczYWRkZjciXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSg0biArIDEpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDEgfSAud3B2LXZpZXctb3V0cHV0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC12aWV3cy12aWV3LWVkaXRvcj0iZDE3MTE4OTZkODY1OWRmMDNhMWFiYmNhOTczYWRkZjciXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSg0biArIDIpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDIgfSAud3B2LXZpZXctb3V0cHV0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC12aWV3cy12aWV3LWVkaXRvcj0iZDE3MTE4OTZkODY1OWRmMDNhMWFiYmNhOTczYWRkZjciXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSg0biArIDMpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDMgfSAud3B2LXZpZXctb3V0cHV0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC12aWV3cy12aWV3LWVkaXRvcj0iZDE3MTE4OTZkODY1OWRmMDNhMWFiYmNhOTczYWRkZjciXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSg0biArIDQpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDQgfSAud3B2LXZpZXctb3V0cHV0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC12aWV3cy12aWV3LWVkaXRvcj0iZDE3MTE4OTZkODY1OWRmMDNhMWFiYmNhOTczYWRkZjciXSAuanMtd3B2LWxvb3Atd3JhcHBlciA+IC50Yi1ncmlkIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC4yNWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC4yNWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC4yNWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC4yNWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwdi1wYWdpbmF0aW9uLW5hdi1saW5rc1tkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtdmlld3Mtdmlldy1wYWdpbmF0aW9uLWJsb2NrPSI5ZTM1MjNmY2VlYTYzOWUyNTEzMzhjNjY5MmZjNzllMSJdIHsgdGV4dC1hbGlnbjogY2VudGVyO2p1c3RpZnktY29udGVudDogY2VudGVyO3BhZGRpbmctdG9wOiAzMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gLndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlLnRiLWltYWdlW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtaW1hZ2U9ImE2NDIyMWU2ZGQ0N2ZiMWE1YzQxNjYyMzZjZmQ3MDc2Il0geyBtYXgtd2lkdGg6IDEwMCU7IH0gIGgyLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSI5MmY2YmY1MGEwN2MxMzAyNTk2MmI5NjRiNDQxYjZkZiJdIGEgIHsgdGV4dC1kZWNvcmF0aW9uOiBub25lOyB9ICBoMi50Yi1oZWFkaW5nW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtaGVhZGluZz0iYjhmYTU4MTgyODVlZDVlNTkwN2RlZGMzNjBjOWQ2ZWIiXSBhICB7IHRleHQtZGVjb3JhdGlvbjogbm9uZTsgfSAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219IC53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZS50Yi1pbWFnZVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWltYWdlPSI2MWExZDkzMTJhOTU1N2JlZjhhMDAzZDcwODc2NWRiOSJdIHsgbWF4LXdpZHRoOiAxMDAlOyB9ICBoMi50Yi1oZWFkaW5nW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtaGVhZGluZz0iYjlhMzFkZjdiNzRjYWMyMjE2ZWIzZDYzMGY4NDhhMzIiXSBhICB7IHRleHQtZGVjb3JhdGlvbjogbm9uZTsgfSBoMi50Yi1oZWFkaW5nW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtaGVhZGluZz0iMTExYzQyM2E1NzAwN2U1OGYwYmY2N2VhZmU4YzY0MWIiXSAgeyBmb250LXNpemU6IDIwcHg7Zm9udC1mYW1pbHk6IE9wZW4gU2Fucztmb250LXdlaWdodDogODAwO2NvbG9yOiByZ2JhKCAyMTcsIDgyLCAzNywgMSApO3BhZGRpbmctbGVmdDogMjBweDsgfSAgaDIudGItaGVhZGluZ1tkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWhlYWRpbmc9IjExMWM0MjNhNTcwMDdlNThmMGJmNjdlYWZlOGM2NDFiIl0gYSAgeyBjb2xvcjogcmdiYSggMjE3LCA4MiwgMzcsIDEgKTt0ZXh0LWRlY29yYXRpb246IG5vbmU7IH0gLnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImZkMmYwZDAzOGYwMjI0NzliNWZkYWIyODNlOTc2YmUyIl0geyBwYWRkaW5nLXRvcDogMjBweDttYXJnaW4tdG9wOiAwO2dyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuMjRmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuNzZmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJmZDJmMGQwMzhmMDIyNDc5YjVmZGFiMjgzZTk3NmJlMiJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJmZDJmMGQwMzhmMDIyNDc5YjVmZGFiMjgzZTk3NmJlMiJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMikgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMiB9ICAudGItZmllbGRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1maWVsZD0iNWE5NTM4ZGEwOWY3M2M3YTE1ZjIwMzliNzQ2NGQ4NzYiXSBhIHsgdGV4dC1kZWNvcmF0aW9uOiBub25lOyB9ICAudGItZmllbGRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1maWVsZD0iNjI2YWJjZjU3MzJlYzcxMTU0OWY5NDc2ODQ1MzRmYmQiXSBhIHsgdGV4dC1kZWNvcmF0aW9uOiBub25lOyB9ICAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219IC53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZS50Yi1pbWFnZVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWltYWdlPSJiN2E2ODQ0MzhlZTA4ZTJkNWQxMWVhM2JmYzViNjljMyJdIHsgbWF4LXdpZHRoOiAxMDAlOyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZS50Yi1pbWFnZVtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWltYWdlPSJiN2E2ODQ0MzhlZTA4ZTJkNWQxMWVhM2JmYzViNjljMyJdIGltZyB7IHBhZGRpbmctdG9wOiAyMHB4O3BhZGRpbmctYm90dG9tOiAyMHB4OyB9ICAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lcltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lcj0iOTkwZTIxMWJmZDlhMWRlOWZmNmVhY2IxMWQ0ZTQ5MWMiXSB7IHBhZGRpbmc6IDQ1cHggMjVweCAxMHB4IDE2cHg7IH0gICAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iZGUwYTg4OWU1NTU5NmRlODY4NWJmNTc3YzQ4ZDAwYWIiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9ImQ5ZDkzZWVhZTgyZTVmMjg0NDMzMjM3Njc0ZDQxZDMwIl0geyBwYWRkaW5nOiAyMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImU4YzllYjY3N2VmNzY3YmE0YjRiNDFiNzYxN2UwOTgzIl0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjY2NWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC4zMzVmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJlOGM5ZWI2NzdlZjc2N2JhNGI0YjQxYjc2MTdlMDk4MyJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJlOGM5ZWI2NzdlZjc2N2JhNGI0YjQxYjc2MTdlMDk4MyJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMikgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMiB9IC50Yi1maWVsZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWZpZWxkPSI4ODk1YjIzMTljNzgxMDAzZTEzZDA4Yjk1NWEzOWE1YiJdIHsgZm9udC1zaXplOiAxMnB4OyB9ICAudGItZmllbGRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1maWVsZD0iODg5NWIyMzE5Yzc4MTAwM2UxM2QwOGI5NTVhMzlhNWIiXSBhIHsgdGV4dC1kZWNvcmF0aW9uOiBub25lOyB9IGgyLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSJmMzkzYjk4ODk5MTk1NTI3ZmZjNjEwNWE3MzcwMGJjNyJdICB7IGxpbmUtaGVpZ2h0OiAxNnB4OyB9ICBoMi50Yi1oZWFkaW5nW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtaGVhZGluZz0iZjM5M2I5ODg5OTE5NTUyN2ZmYzYxMDVhNzM3MDBiYzciXSBhICB7IHRleHQtZGVjb3JhdGlvbjogbm9uZTsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lcltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lcj0iZWQzODMyYWE2MjAxY2JlYzViMWU1YjkwMmRjMDY3ZTIiXSB7IHBhZGRpbmc6IDI1cHg7IH0gLnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImI0MzIxNzE4MTI0MGMwODQyMzdmYjlmM2FhMzc0OGI5Il0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjI3MzMzMzMzMzMzMzMzZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjQ0MzMzMzMzMzMzMzMzZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjI4MzMzMzMzMzMzMzMzZnIpO2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDogMnB4O2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iYjQzMjE3MTgxMjQwYzA4NDIzN2ZiOWYzYWEzNzQ4YjkiXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSgzbiArIDEpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDEgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iYjQzMjE3MTgxMjQwYzA4NDIzN2ZiOWYzYWEzNzQ4YjkiXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSgzbiArIDIpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDIgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iYjQzMjE3MTgxMjQwYzA4NDIzN2ZiOWYzYWEzNzQ4YjkiXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSgzbiArIDMpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDMgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iNjE5MWE5ZGNjYjEwZjNhZWIzYmE0YTljNTE3YWIyZTAiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWJ1dHRvbntjb2xvcjojZjFmMWYxfS50Yi1idXR0b24tLWxlZnR7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpsZWZ0fS50Yi1idXR0b24tLWNlbnRlcnt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmNlbnRlcn0udGItYnV0dG9uLS1yaWdodHt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOnJpZ2h0fS50Yi1idXR0b25fX2xpbmt7Y29sb3I6aW5oZXJpdDtjdXJzb3I6cG9pbnRlcjtkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1ibG9jaztsaW5lLWhlaWdodDoxMDAlO3RleHQtZGVjb3JhdGlvbjpub25lICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpjZW50ZXI7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjphbGwgMC4zcyBlYXNlfS50Yi1idXR0b25fX2xpbms6aG92ZXIsLnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fbGluazpmb2N1cywudGItYnV0dG9uX19saW5rOnZpc2l0ZWR7Y29sb3I6aW5oZXJpdH0udGItYnV0dG9uX19saW5rOmhvdmVyIC50Yi1idXR0b25fX2NvbnRlbnQsLnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fbGluazpmb2N1cyAudGItYnV0dG9uX19jb250ZW50LC50Yi1idXR0b25fX2xpbms6dmlzaXRlZCAudGItYnV0dG9uX19jb250ZW50e2ZvbnQtZmFtaWx5OmluaGVyaXQ7Zm9udC1zdHlsZTppbmhlcml0O2ZvbnQtd2VpZ2h0OmluaGVyaXQ7bGV0dGVyLXNwYWNpbmc6aW5oZXJpdDt0ZXh0LWRlY29yYXRpb246aW5oZXJpdDt0ZXh0LXNoYWRvdzppbmhlcml0O3RleHQtdHJhbnNmb3JtOmluaGVyaXR9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fY29udGVudHt2ZXJ0aWNhbC1hbGlnbjptaWRkbGU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjphbGwgMC4zcyBlYXNlfS50Yi1idXR0b25fX2ljb257dHJhbnNpdGlvbjphbGwgMC4zcyBlYXNlO2Rpc3BsYXk6aW5saW5lLWJsb2NrO3ZlcnRpY2FsLWFsaWduOm1pZGRsZTtmb250LXN0eWxlOm5vcm1hbCAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1idXR0b25fX2ljb246OmJlZm9yZXtjb250ZW50OmF0dHIoZGF0YS1mb250LWNvZGUpO2ZvbnQtd2VpZ2h0Om5vcm1hbCAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1idXR0b25fX2xpbmt7YmFja2dyb3VuZC1jb2xvcjojNDQ0O2JvcmRlci1yYWRpdXM6MC4zZW07Zm9udC1zaXplOjEuM2VtO21hcmdpbi1ib3R0b206MC43NmVtO3BhZGRpbmc6MC41NWVtIDEuNWVtIDAuNTVlbX0gLnRiLWJ1dHRvbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWJ1dHRvbj0iNzJmMjhiODNlZDhmZWE0ZjgzMDJlNGQ4ZjNkOGRkMTciXSAudGItYnV0dG9uX19pY29uIHsgZm9udC1mYW1pbHk6IGRhc2hpY29uczsgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iYTgyYTc1NzBhODY3MzM4YTU2MTAwMDAyNzg0YTI3ZjAiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjVkYWU5YTZhYmRkNTRjZGI3Y2E0MmQyYzYxMmU2OWJhIl0geyBwYWRkaW5nLXJpZ2h0OiAzMHB4O2Rpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iZDFmODVhYzAzNTgwMGNlY2U0MjQwMTg2N2E2MDA3ZGIiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMDcxNGFjMzM1YmRkZmE2NDk4MDBiYjcyYWI2ZTQyM2QiXSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuNjRmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuMzZmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSIwNzE0YWMzMzViZGRmYTY0OTgwMGJiNzJhYjZlNDIzZCJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSIwNzE0YWMzMzViZGRmYTY0OTgwMGJiNzJhYjZlNDIzZCJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMikgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMiB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSJmNmUwZWIwYTU5MzFiZDBmOTQwNDI1NzMxYjYzMzczNSJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iMzAzNGZiZTg4NmMxMTA1NGU5NWI0NmIwOWQzZTQxMTIiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iOTFiMmQ5ODJiNTQxMDdhNzRkZDY4M2M3OWFkMzc3YWUiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSBAbWVkaWEgb25seSBzY3JlZW4gYW5kIChtYXgtd2lkdGg6IDc4MXB4KSB7ICAgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30udGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfS50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwdi12aWV3LW91dHB1dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtdmlld3Mtdmlldy1lZGl0b3I9ImQxNzExODk2ZDg2NTlkZjAzYTFhYmJjYTk3M2FkZGY3Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoM24gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwdi12aWV3LW91dHB1dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtdmlld3Mtdmlldy1lZGl0b3I9ImQxNzExODk2ZDg2NTlkZjAzYTFhYmJjYTk3M2FkZGY3Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoM24gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLndwdi12aWV3LW91dHB1dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtdmlld3Mtdmlldy1lZGl0b3I9ImQxNzExODk2ZDg2NTlkZjAzYTFhYmJjYTk3M2FkZGY3Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoM24gKyAzKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAzIH0gLndwdi12aWV3LW91dHB1dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtdmlld3Mtdmlldy1lZGl0b3I9ImQxNzExODk2ZDg2NTlkZjAzYTFhYmJjYTk3M2FkZGY3Il0gLmpzLXdwdi1sb29wLXdyYXBwZXIgPiAudGItZ3JpZCB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuMzMzM2ZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC4zMzMzZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjMzMzNmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gIC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gIC50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJmZDJmMGQwMzhmMDIyNDc5YjVmZGFiMjgzZTk3NmJlMiJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC41ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJmZDJmMGQwMzhmMDIyNDc5YjVmZGFiMjgzZTk3NmJlMiJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJmZDJmMGQwMzhmMDIyNDc5YjVmZGFiMjgzZTk3NmJlMiJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMikgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMiB9ICAgIC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gIC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSJkZTBhODg5ZTU1NTk2ZGU4Njg1YmY1NzdjNDhkMDBhYiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfS50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImU4YzllYjY3N2VmNzY3YmE0YjRiNDFiNzYxN2UwOTgzIl0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuNWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImU4YzllYjY3N2VmNzY3YmE0YjRiNDFiNzYxN2UwOTgzIl0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImU4YzllYjY3N2VmNzY3YmE0YjRiNDFiNzYxN2UwOTgzIl0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gICAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfS50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJiNDMyMTcxODEyNDBjMDg0MjM3ZmI5ZjNhYTM3NDhiOSJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC4zMzMzZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjMzMzNmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuMzMzM2ZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImI0MzIxNzE4MTI0MGMwODQyMzdmYjlmM2FhMzc0OGI5Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoM24gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImI0MzIxNzE4MTI0MGMwODQyMzdmYjlmM2FhMzc0OGI5Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoM24gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImI0MzIxNzE4MTI0MGMwODQyMzdmYjlmM2FhMzc0OGI5Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoM24gKyAzKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAzIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjYxOTFhOWRjY2IxMGYzYWViM2JhNGE5YzUxN2FiMmUwIl0geyBkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IC50Yi1idXR0b257Y29sb3I6I2YxZjFmMX0udGItYnV0dG9uLS1sZWZ0e3RleHQtYWxpZ246bGVmdH0udGItYnV0dG9uLS1jZW50ZXJ7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbi0tcmlnaHR7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpyaWdodH0udGItYnV0dG9uX19saW5re2NvbG9yOmluaGVyaXQ7Y3Vyc29yOnBvaW50ZXI7ZGlzcGxheTppbmxpbmUtYmxvY2s7bGluZS1oZWlnaHQ6MTAwJTt0ZXh0LWRlY29yYXRpb246bm9uZSAhaW1wb3J0YW50O3RleHQtYWxpZ246Y2VudGVyO3RyYW5zaXRpb246YWxsIDAuM3MgZWFzZX0udGItYnV0dG9uX19saW5rOmhvdmVyLC50Yi1idXR0b25fX2xpbms6Zm9jdXMsLnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fbGluazp2aXNpdGVke2NvbG9yOmluaGVyaXR9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fbGluazpob3ZlciAudGItYnV0dG9uX19jb250ZW50LC50Yi1idXR0b25fX2xpbms6Zm9jdXMgLnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fY29udGVudCwudGItYnV0dG9uX19saW5rOnZpc2l0ZWQgLnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fY29udGVudHtmb250LWZhbWlseTppbmhlcml0O2ZvbnQtc3R5bGU6aW5oZXJpdDtmb250LXdlaWdodDppbmhlcml0O2xldHRlci1zcGFjaW5nOmluaGVyaXQ7dGV4dC1kZWNvcmF0aW9uOmluaGVyaXQ7dGV4dC1zaGFkb3c6aW5oZXJpdDt0ZXh0LXRyYW5zZm9ybTppbmhlcml0fS50Yi1idXR0b25fX2NvbnRlbnR7dmVydGljYWwtYWxpZ246bWlkZGxlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246YWxsIDAuM3MgZWFzZX0udGItYnV0dG9uX19pY29ue3RyYW5zaXRpb246YWxsIDAuM3MgZWFzZTtkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1ibG9jazt2ZXJ0aWNhbC1hbGlnbjptaWRkbGU7Zm9udC1zdHlsZTpub3JtYWwgIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItYnV0dG9uX19pY29uOjpiZWZvcmV7Y29udGVudDphdHRyKGRhdGEtZm9udC1jb2RlKTtmb250LXdlaWdodDpub3JtYWwgIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItYnV0dG9uX19saW5re2JhY2tncm91bmQtY29sb3I6IzQ0NDtib3JkZXItcmFkaXVzOjAuM2VtO2ZvbnQtc2l6ZToxLjNlbTttYXJnaW4tYm90dG9tOjAuNzZlbTtwYWRkaW5nOjAuNTVlbSAxLjVlbSAwLjU1ZW19LndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49ImE4MmE3NTcwYTg2NzMzOGE1NjEwMDAwMjc4NGEyN2YwIl0geyBkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSI1ZGFlOWE2YWJkZDU0Y2RiN2NhNDJkMmM2MTJlNjliYSJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjA3MTRhYzMzNWJkZGZhNjQ5ODAwYmI3MmFiNmU0MjNkIl0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcikgbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuNWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjA3MTRhYzMzNWJkZGZhNjQ5ODAwYmI3MmFiNmU0MjNkIl0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjA3MTRhYzMzNWJkZGZhNjQ5ODAwYmI3MmFiNmU0MjNkIl0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49ImY2ZTBlYjBhNTkzMWJkMGY5NDA0MjU3MzFiNjMzNzM1Il0geyBkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIzMDM0ZmJlODg2YzExMDU0ZTk1YjQ2YjA5ZDNlNDExMiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219IH0gQG1lZGlhIG9ubHkgc2NyZWVuIGFuZCAobWF4LXdpZHRoOiA1OTlweCkgeyAgIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99LnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30udGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfS50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cHYtdmlldy1vdXRwdXRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LXZpZXdzLXZpZXctZWRpdG9yPSJkMTcxMTg5NmQ4NjU5ZGYwM2ExYWJiY2E5NzNhZGRmNyJdICA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSgxbisxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwdi12aWV3LW91dHB1dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtdmlld3Mtdmlldy1lZGl0b3I9ImQxNzExODk2ZDg2NTlkZjAzYTFhYmJjYTk3M2FkZGY3Il0gLmpzLXdwdi1sb29wLXdyYXBwZXIgPiAudGItZ3JpZCB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDFmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gIC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gIC50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJmZDJmMGQwMzhmMDIyNDc5YjVmZGFiMjgzZTk3NmJlMiJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImZkMmYwZDAzOGYwMjI0NzliNWZkYWIyODNlOTc2YmUyIl0gID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDFuKzEpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDEgfSAgICAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99ICAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iZGUwYTg4OWU1NTU5NmRlODY4NWJmNTc3YzQ4ZDAwYWIiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30udGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfS50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSJlOGM5ZWI2NzdlZjc2N2JhNGI0YjQxYjc2MTdlMDk4MyJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImU4YzllYjY3N2VmNzY3YmE0YjRiNDFiNzYxN2UwOTgzIl0gID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDFuKzEpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDEgfSAgIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9ImI0MzIxNzE4MTI0MGMwODQyMzdmYjlmM2FhMzc0OGI5Il0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iYjQzMjE3MTgxMjQwYzA4NDIzN2ZiOWYzYWEzNzQ4YjkiXSAgPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMW4rMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSI2MTkxYTlkY2NiMTBmM2FlYjNiYTRhOWM1MTdhYjJlMCJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItYnV0dG9ue2NvbG9yOiNmMWYxZjF9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbi0tbGVmdHt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmxlZnR9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbi0tY2VudGVye3RleHQtYWxpZ246Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1idXR0b24tLXJpZ2h0e3RleHQtYWxpZ246cmlnaHR9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fbGlua3tjb2xvcjppbmhlcml0O2N1cnNvcjpwb2ludGVyO2Rpc3BsYXk6aW5saW5lLWJsb2NrO2xpbmUtaGVpZ2h0OjEwMCU7dGV4dC1kZWNvcmF0aW9uOm5vbmUgIWltcG9ydGFudDt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmNlbnRlcjt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOmFsbCAwLjNzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fbGluazpob3ZlciwudGItYnV0dG9uX19saW5rOmZvY3VzLC50Yi1idXR0b25fX2xpbms6dmlzaXRlZHtjb2xvcjppbmhlcml0fS50Yi1idXR0b25fX2xpbms6aG92ZXIgLnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fY29udGVudCwudGItYnV0dG9uX19saW5rOmZvY3VzIC50Yi1idXR0b25fX2NvbnRlbnQsLnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fbGluazp2aXNpdGVkIC50Yi1idXR0b25fX2NvbnRlbnR7Zm9udC1mYW1pbHk6aW5oZXJpdDtmb250LXN0eWxlOmluaGVyaXQ7Zm9udC13ZWlnaHQ6aW5oZXJpdDtsZXR0ZXItc3BhY2luZzppbmhlcml0O3RleHQtZGVjb3JhdGlvbjppbmhlcml0O3RleHQtc2hhZG93OmluaGVyaXQ7dGV4dC10cmFuc2Zvcm06aW5oZXJpdH0udGItYnV0dG9uX19jb250ZW50e3ZlcnRpY2FsLWFsaWduOm1pZGRsZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOmFsbCAwLjNzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9faWNvbnt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOmFsbCAwLjNzIGVhc2U7ZGlzcGxheTppbmxpbmUtYmxvY2s7dmVydGljYWwtYWxpZ246bWlkZGxlO2ZvbnQtc3R5bGU6bm9ybWFsICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9faWNvbjo6YmVmb3Jle2NvbnRlbnQ6YXR0cihkYXRhLWZvbnQtY29kZSk7Zm9udC13ZWlnaHQ6bm9ybWFsICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWJ1dHRvbl9fbGlua3tiYWNrZ3JvdW5kLWNvbG9yOiM0NDQ7Ym9yZGVyLXJhZGl1czowLjNlbTtmb250LXNpemU6MS4zZW07bWFyZ2luLWJvdHRvbTowLjc2ZW07cGFkZGluZzowLjU1ZW0gMS41ZW0gMC41NWVtfS53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSJhODJhNzU3MGE4NjczMzhhNTYxMDAwMDI3ODRhMjdmMCJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iNWRhZTlhNmFiZGQ1NGNkYjdjYTQyZDJjNjEyZTY5YmEiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfS50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSIwNzE0YWMzMzViZGRmYTY0OTgwMGJiNzJhYjZlNDIzZCJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjA3MTRhYzMzNWJkZGZhNjQ5ODAwYmI3MmFiNmU0MjNkIl0gID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDFuKzEpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDEgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iZjZlMGViMGE1OTMxYmQwZjk0MDQyNTczMWI2MzM3MzUiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjMwMzRmYmU4ODZjMTEwNTRlOTViNDZiMDlkM2U0MTEyIl0geyBkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gfSA=

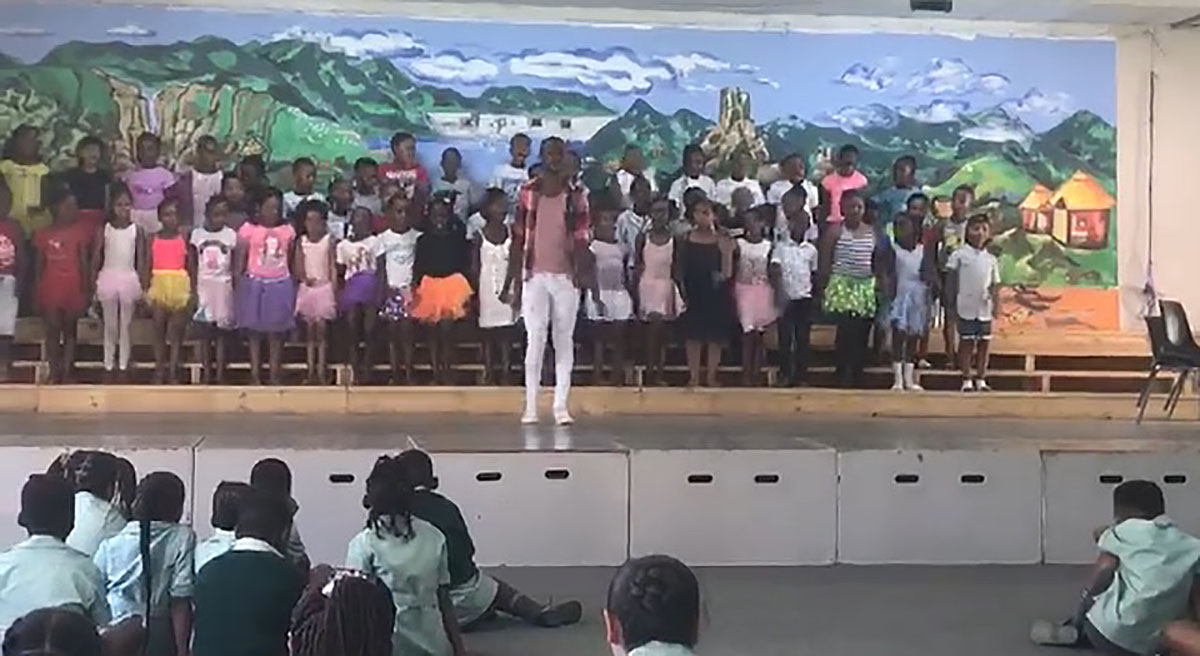

John Minnaar, teacher and conductor, Maseru Preparatory School

The history of human struggle and social unrest in southern Africa is well documented; the struggle gave birth to a new era of growth and potential for its people. One might say that in the wake of South Africa’s newfound freedom from Apartheid, democracy opened many doors to Black South Africans. Within that greater context, I share my own musical journey as a snapshot of three decades of music, equity, and opportunity in South Africa and Lesotho.

My journey began in 1999 as a student with the Mangaung String Programme (MSP) in Bloemfontein, which has its roots in the original Free State String Orchestra, run by the Free State Education Department. Previously known as the Bochabela String Orchestra, the prestigious program was initiated by the Free State Musicon in July 1998 under the tutelage of Peter Guy. The MSP focuses its work primarily on children from disadvantaged communities, and a great part of the Free State Province receives weekly lessons from the program. Teachers travel to various local areas to teach violin, viola, cello, and double bass, forming orchestras of various levels across the region. I was first a learner and then an apprentice with MSP; fascinated by the stringed instruments, I was fortunate to learn them all. Though I primarily play the cello, I also learned piano, double bass, violin, viola, and clarinet. With the MSP, I learned to teach, care, and perform confidently and enthusiastically, with conviction and grace.

I have many fond memories of my time with the organization, which has appeared on national and international television and performed as guests both nationally and internationally. The MSP is a shining star for South African music education, having received SAMRO’s Best Development Program Award for three years in a row. The success of the Mangaung String Programme was essential to the future of South Africa’s music programs.

As the music for social change movement was just beginning to take off, I felt very fortunate to be offered a teaching position at the Northern Cape Province’s Kimberley Academy of Music in January 2010. It was a new beginning, away from my mentors, peers, family, and friends. At every stage of teaching—and, more importantly, learning—I applied the methodology I learned at the MSP. In particular, I applied what I had learned from my students. Students are great teachers—they effortlessly evaluate one’s abilities, patience, passion, and ability to explore new horizons. This was a period of tremendous growth for me personally, and even more so for the country.

MIAGI European tour for the 2018 Mandela Centenary. Credit John Minnaar

Throughout this time, I was influenced heavily by an organization that embodies the spirit of South Africa’s musical and social growth: MIAGI (Music Is A Great Investment). The MIAGI Youth Orchestra has played a huge role in my development as both a musician and a teacher. All of us are different—different religions, cultures, sexualities, ethnicities, social statuses, and more. And yet we all assembled because of music. To mention a few of our very own composers within MIAGI: Tshepo Tsotetsi, Ilke Lea Alexander, Monique van Willingh, Viwe Mkhizwana—all conveying their ethnicity, talents, passions, and inspirations through music. As MIAGI grew, it was liberating and exciting to see so many barriers broken. I am grateful especially to Robert Brooks, who made it all possible for the past 16 years.

My career eventually brought me to the small country of Lesotho, near the Bloemfontein region of South Africa, where I continue to teach and conduct today. Bloemfontein is steps ahead in many aspects—more music programs, more music studios, more catering to musicians at higher learning institutions. When observing Lesotho’s progress through the lens of its South African neighbor, it can feel as if the country is yet to be fully on board. Yet so much good still happens there, including at the Maseru Preparatory School in Maseru, Lesotho, where I now serve as a music teacher and choir conductor.

At Maseru Prep, class sizes range between 18 and 24 students, from grades 1–6; there are about 19 classes in total. The Junior Choir consists of 40 members and the Senior Choir about 50 members. The school also offers individual lessons and occasional one-hour group lessons for groups of five, where we cover both practical and theoretical work.

As in most places, Lesotho’s citizens are incredibly talented. The sad reality is these talents are often unnoticed, undeveloped, and unrecognized. Put simply, there are not enough institutions to develop and cater to all these talents. So many learners, both at and outside Maseru Prep, are on a waiting list for instrumental lessons. To my great devastation, I’m not able to accommodate them all. As much as it hurts me, I can’t even begin to comprehend their own sense of loss.

Recently, a colleague, friend, and sister through the Mangaung String Programme, violinist and violist Sehle Mosole, presented a workshop as part of her Bachelor of Music degree at the University of the Free State. She majors in education, and she took the initiative to present a workshop based on Kodály teaching techniques in Lesotho, her home country. How rewarding for all attendees. In many respects, it awakened me; if we strive to attend workshops and learn from experts in our fields, we can collectively overcome some of the challenges we face.

Sehle Mosole and John Minnaar after the 2019 Maseru Prep Christmas concert. Credit John Minnaar

Still, Lesotho should and must invest in music education broadly. A few existing institutions or private studios cannot cater to all—they need support. I take my hat off to the individuals who successfully changed lives and continue to do so with music, with almost no support and minimal resources. I am humbled and honored to call them friends and colleagues. I have truly witnessed miracles.

When I think of the work that lies ahead for those of us in the region, I think about the two words that form the term “social change.” “Change” denotes the transformation of one thing to another—and in classical music, a lot of change has transpired over the centuries. Most inspiring of all is who now gets to play these instruments: everyone. Whatever one’s race or background, all are equal on stage. In my experience, I have found this to be truer in Bloemfontein than in Lesotho. Which only means that there is more work to do.

That is where the “social” part comes in. Music’s beauty lies in how it brings us together, allowing us to communicate with one another without speaking any words at all. Thus, “social change” is the shift that allows people to focus on their similarities more than their differences. That is my dream for Lesotho, and for all of Africa.

God bless Africa and her people!